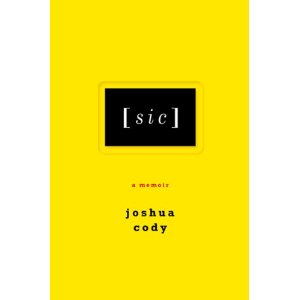

[sic] by Joshua Cody

Joshua Cody’s new memoir [sic] is partly the story of how he—a young man living in New York City, a composer, a descendant of Buffalo Bill Cody—was diagnosed with cancer (a lymphoma of some sort, he never really says) and the treatment didn’t work and he had to get a bone marrow transplant, but really it’s mostly the story of what it’s like to be inside Joshua Cody’s head. One thing fiction (and memoir) teaches us, one of its greatest assets is that it’s possible (and good) to think beyond our selves—to actively try to adopt another’s point of view. David Foster Wallace says it way better than me: “I guess a big part of serious fiction’s purpose is to give the reader, who like all of us is sort of marooned in her own skull, to give her imaginative access to other selves.†And then in the same breath Wallace goes on to explain some of the same stuff about suffering that Joshua Cody is dealing with in [sic]:

Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience, more like a sort of “generalization†of suffering. Does this make sense? We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might just be that simple.

But we’re getting a little ahead of our selves here. Both Wallace and Cody struggle with knowing something long and complex and looking at it, think “How do I tell this story? Where do you begin? How about this little bit here? Is that really the beginning? Bear with me while I go back and explain…†This struggle to deal with narrative and the flow of the story/plot reflects a lifelong struggle to live in a way that is not constantly fracturing and forking off in different directions. But that does not mean the story and the life are formless. Cody is a trained composer, a musician. He is deeply concerned about form and framing.

Cody is clearly a David Foster Wallace fan—and Wallace’s struggle with depression and eventual suicide haunt him. “Our greatest writer. As if I wasn’t thinking of him during that whole thing. My God. As if he hadn’t helped.” Cody contemplates killing himself (in a scene reminiscent of The Royal Tenenbaums), standing in front of a mirror, well actually “it was me between two mirrors, producing an infinite line of selves, like at the end of Citizen Kane.” And the crucial question he finds before him is: “How do we position suffering in human life?” And this is where it gets interesting, because maybe we think of a cancer memoir as one where the writer is faced with death and discovers the beauty of life or some such thing. But Cody, raised on aesthetics, says “I do love being alive, sitting here with this first edition of the Cantos my father gave me—and maybe, you may well argue, the house is too thick and the paintings a shade too oiled (and the old voice lifts itself, weaving an endless sentence), and you may well be right—but my goodness, fuck you, I happen to be so happy here with all these gifts and words and all these selves.” And if you yourself have been in this position of having a doctor refer to your imminent death and the chemotherapy you need to receive and if you have browsed the bookstore’s self-help-dying-cancer shelves and thought “pure dreck,” then Joshua Cody is right there with you:

If there are some people who require disease to teach them such things then fine, but I am not, was not one of those those, thank you very much. I loved life and found beauty and sources of pleasure in things on the outside and on the inside, and illness was not an opportunity for existential awakenings, it was the very opposite of beauty or grace, it was a harrowing, a descensus: and then it went down.

More than Wallace, this attitude (and the opening scene of receiving a chemotherapy treatment) call to mind, to me at least, Walter White and Breaking Bad. The nearness of death accentuates the urgency of life while also accentuating its inherent suffering, its opposition to neat and tidy endings. Both Cody and Walter White show us that the relatively commonplace occurrence of cancer can lead not only to introspection and carpe diem, but also to sad risk-taking and (personal and public) failures.

Wallace says “What the really great artists do is they’re entirely themselves. They’re entirely themselves, they’ve got their own vision, they have their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings.†Joshua Cody is a great artist, entirely himself, and in [sic], while we watch him flay his own nerve endings and try to mend them back together again, we see glimpses of our selves.